OSCAR GOES CUCKOO

OSCAR GOES CUCKOO

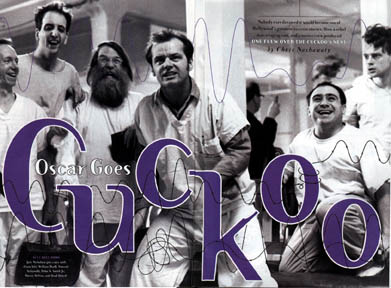

On Oscar night 25 years ago, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest pulled off a feat no film had accomplished since Frank Capra's It Happened One Night in 1935: It swept the top five categories at the Academy Awards.

Accepting the statuette for Best Picture was an unlikely pair of fledgling producers: Saul Zaentz, a Berkeley, Calif., jazz-record producer, and Michael Douglas, a struggling second-generation actor best known for the TV cop show The Streets of San Francisco. Meanwhile, Milos Forman, a down-on-his-luck Czech émigré whose American debut had flopped five years ago, took home Best Director. Two screenwriters who had never so much as met each other -- Lawrence Hauben and Bo Goldman -- shared the stage as cowinners of best screenplay. And then there were the film's stars: Louise Fletcher, the sixth choice for the movie's villainous leading lady, won Best Actress; and four-time nominee -- and four-time loser -- Jack Nicholson was finally anointed Best Actor.

But despite all of Cuckoo's Nest's gold-plated glory at the Academy Awards, one person was curiously absent from the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion on March 29, 1976 -- Kirk Douglas. Watching the ceremony from his home in Palm Springs, Calif., the actor, then 59, savored the sweet taste of vindication from afar. After all, Douglas had struggled for a decade to adapt Ken Kesey's allegorical novel -- about the patients in a mental hospital and their rebellion against the system -- into a movie. A struggle that he jokes almost drove him insane. So, on the silver anniversary of Cuckoo's Nest's golden night at the Oscars, here is the behind-the-scenes story of how one Best Picture winner was almost never a picture at all...

By the beginning of the 1960s, Kirk Douglas had already appeared in such classics as Champion, Lust For Life, and Spartacus. One of the first Hollywood stars to cross over into the position of producer, Douglas saw himself in the role of Cuckoo's Nest's charismatic, crazy-like-a-fox inmate R.P. McMurphy the moment he read Kesey's 1962 novel.

"The studios are not necessarily brilliant, and this was something new," says Douglas. "It dealt with something that might make some people uncomfortable. So I thought, I'll do it first as a play." The critics were less than kind to the production. It closed after six months. "My agent was furious at me because I was passing up all the offers for movies," the actor recalls. So Douglas returned to Hollywood hurt and confused: "I said to my wife, 'I gave them a classic and they don't even know it.'"

By the end of the '60s, Douglas had virtually given up on turning Cuckoo's Nest into a film, despite the fact that in the meantime, Kesey's novel had become a hip totem of the counterculture. Over the years, others had shown interest in taking the producing reins, including a young actor named Jack Nicholson. But nothing happened until Douglas' son Michael -- at the time a minor actor knocking around in such unforgettable films as Hail, Hero! -- approached his father about the long-stalled project. "He was considering selling the motion picture rights because he'd tried for a while," says Michael. "So I asked him if I could run with it and see if I could try to get the picture set up. I was an actor who wasn't getting a lot of work and I thought I'd devote my time to trying to get the picture made."

While in San Francisco shooting The Streets of San Francisco, Michael Douglas reached out to Saul Zaentz, the cherubic jazzbo head of Fantasy Records in Berkeley, who had also expressed interest in Cuckoo's Nest years earlier. "Kirk didn't want to sell it unless he starred in it," recalls Zaentz. "So nothing came of it until 1971, when Michael Douglas called us up. He asked if we were still interested."

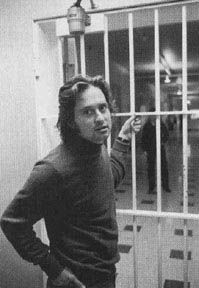

Milos Forman, who fled his homeland in 1968 when Soviet tanks rolled into Prague, had made several well-regarded films in Czechoslovakia, but his first Hollywood movie, 1971's Taking Off -- a satire of the hippie movement -- bombed. Living hand-to-mouth at New York's bohemian enclave the Chelsea Hotel, Forman was unable to pay his rent as he awaited his next directing gig. "Strangely enough, I wasn't panicking because I knew I couldn't go back to Czechoslovakia," says Forman. "And then comes this book in an envelope from Saul and Michael. And in my youthful arrogance, I thought, 'Of course I'm the right director because the book is about what I just left -- the totalitarian system.'"

After several far-out script drafts by Kesey, Lawrence Hauben -- a friend of Michael Douglas' -- had been tapped to work on the screenplay. (Hauben died of cancer in 1985.) While Hauben's script was structurally sound, Zaentz thought it lacked heart. Forman's agent suggested that Bo Goldman, a novice screenwriter and librettist he also represented, take a stab at it. "They came to me because I was cheap," laughs Goldman. "I hadn't really done anything and I was starting to lose hope. I was going to give up and go back out to Long Island with my wife and run a fish store in Sagaponack."

For the next eight weeks, Goldman would show up at Forman's room at L.A.'s Sunset Marquis to hammer out the script. At the time, the hotel was better known as Ellis Island West due to its reputation as an outpost for vagrant writers and second-rate actors who'd just moved to Hollywood. "He had on a maroon bathing suit and a 1965 world's fair shirt, and that costume never varied over the two months we worked on the script in that room," says Goldman. The routine rarely changed either. Arriving at 10 each morning, Goldman would have to wait over an hour before the cigar-smoking Forman would offer him Czech beer, black bread, and cabbage out of a mason jar.

With no choice but to make Cuckoo's Nest on their own, Zaentz and Douglas scratched together $4 million, with a significant chunk going to its star, Jack Nicholson, to sign on in the starring role. "Of course I still wanted to play McMurphy," says Kirk Douglas. "But I didn't want to put any conditions on the movie. They had to do what they thought."

Jack Nicholson was always Forman's first choice to play McMurphy. Coming off Oscar-nominated performances in Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces, The Last Detail, and Chinatown, Nicholson was an actor in demand. And when they were told they'd have to wait several months for Nicholson to wrap another movie, they began to bat around potential backups such as Gene Hackman and Marlon Brando. The one person who wasn't considered was Kirk Douglas. "We all somehow felt without speaking about it that he was already too old," says Forman, who believed Nicholson was McMurphy.

Nicholson agreed. "My only hesitation about playing the part was that this guy was described as an enormous redhead. And that can throw you off when you're reading something," says Nicholson. "But as far as the interior of the character...I knew I could play him to a T. I didn't have a lot of reservations about anything in those days."

After a brief television career in the late '50s, Louise Fletcher had all but dropped out of acting. Not that it would have mattered much. For the control-freak character of Nurse Ratched, the filmmakers considered just about every other actress-of-certain-age working: Colleen Dewhurst, Geraldine Page, Anne Bancroft, Ellen Burstyn, and Angela Lansbury were all offered the role and flatly turned it down. "You have to remember at that time it was not politically correct for women to play villains," says Michael Douglas. "It was the beginning of the women's movement." But then Nicholson suggested Fletcher after seeing her comeback performance in Robert Altman's Thieves Like Us. "She just played a real dishwater-eyed kind of killer and I thought she was the right actress," says Nicholson.

For the other supporting players -- Brad Dourif, Danny DeVito, Christopher Lloyd, Vincent Schiavelli, William Redstone, William Duell, Sidney Lassick, and Will Sampson as Chief -- Zaentz says they saw 1,260 actors from New York City and Los Angeles: "They had about as much film experience as you could fit in the navel of a flea."

In January 1975, the cast and crew of Cuckoo's Nest headed to the Oregon State Hospital in Salem for the 11-week shoot. Once there, they added a few other faces to the cast. "The head of the hospital said he thought it would be therapy for some of his patients to be in the film," says Forman. "It humbled everybody to see the lives of these poor souls." Nicholson is still haunted by one particular late-night encounter at the hospital. "I'll never forget being in the maximum-security ward upstairs watching shock treatments at four in the morning," he says. "They gave three of them that morning, and I watched them all because I wanted to get it right. That atmosphere does sink in on you."

When asked for his version of events, Kesey responded to Entertainment Weekly with an e-mail: "I've never seen the movie. During the lawsuit one of the lawyers says, 'Ah, you'll be the first in line to see this flick' -- to which I responded, 'I swear to God I won't see it!' And I consider it one of the smartest things I never did."

On the strength of the film's dailies, Zaentz and Douglas got United Artists to distribute the film. Needless to say, the studio received a far less lucrative deal than it would have gotten had it signed on before the shoot. Then again, United Artists had no idea that the $4 million film would rack up close to $200 million domestically and become the second-highest grossing film of the year behind Jaws. "United Artists predicted that the film would make $10 million -- which I thought was wonderful," says Forman. "Then the next week they'd say, 'No, it might do 15!' Then the next week, they said, 'No, it might do 20!'"

Thanks to a lack of studio interest in the film before shooting started, the filmmakers now all stood to get rich off Cuckoo's Nest -- even Kesey, who had 2 1/2 points. "I did tremendous," cracks Nicholson, while Forman recalls being thrilled that he could finally pay off his back rent at the Chelsea Hotel. Still, Kirk Douglas says the real payoff was proving wrong those who'd initially brushed him off. "Revenge is the right word," says Douglas.

In February 1976, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest was rewarded by the Academy with nine Oscar nominations. Its competition in the Best Picture category was Barry Lyndon, Dog Day Afternoon, Jaws, and Nashville. Nicholson now says he knew that he -- and the film -- would clean up. "I was due, and I just felt like I would win," he says, referring to his four previous Oscar losses. But Michael Douglas doesn't remember Nicholson being so cocky at the time. "Jack didn't want to go. He just didn't want to go through the whole process of going there one more time for a nomination. I remember he was sitting right in front of me, and the first four awards we were up for, we lost. And Jack turned to me and said, 'Mikey, I told ya, I told ya. You see what's happenin'?'"

But beginning with the screenwriting award, the landslide kicked in. "That was the tip-off," recalls Forman, whose twin sons -- he hadn't seen them in eight years -- had been allowed to leave Czechoslovakia to attend the ceremony with him. When Fletcher won her Best Actress Oscar, she indelibly brought down the house with an acceptance speech delivered in sign language to her deaf parents. At the end of the evening, as all the winners were gathered on stage, Nicholson turned to Goldman. "Jack hugged me and he leaned in to tell me something -- and I thought it was going to be something deep -- and he said, 'Gold, pure gold!'" laughs Goldman. "That's when I realized he had 10 percent of the gross." In fact, in his acceptance speech, Nicholson thanked Mary Pickford -- the first actress to take a percentage of a film's earnings.

Years later, in his autobiography The Ragman's Son, Kirk Douglas wrote: "Cuckoo's Nest is one of the biggest disappointments of my life. I made more money from that film than any I acted in. And I would gladly give back every cent if I could have played that role." Asked about his feelings now, on the 25th anniversary of its Oscar sweep, Douglas adds, "If Jack was lousy in it, I would have said, 'What a mistake they made!' But he got an Oscar, so maybe I would have been wrong in the part."

As for the man who got to play McMurphy in the end, Nicholson says, "Well, you know, if Kirk hadn't held on to Cuckoo's Nest with that granitelike jaw of his, none of us would have been there."

Copyright February 2001 Entertainment Weekly.

From Entertainment Weekly's Special Oscar Guide 2001

by CHRIS NASHAWATY

Purchasing the rights from the mercurial merry prankster Kesey, Douglas hired writer Dale Wasserman to adapt the book for Broadway while he scrambled full-time to get Hollywood studios interested. After all, how could they not jump with Kirk Douglas attached? Looking back at his decade-long string of rejections, Douglas says, "What can I say? They didn't jump.

Purchasing the rights from the mercurial merry prankster Kesey, Douglas hired writer Dale Wasserman to adapt the book for Broadway while he scrambled full-time to get Hollywood studios interested. After all, how could they not jump with Kirk Douglas attached? Looking back at his decade-long string of rejections, Douglas says, "What can I say? They didn't jump.

What Forman didn't know what that Zaentz and Douglas had already met with virtually every other director in Hollywood. The producers set up a meeting with the Czech director at Yamato's -- a Japanese restaurant in Los Angeles' Century City. "We came in about 8 p.m. for dinner and we closed up the joint like in old movies where the waiters circle the table emptying the ashtrays

and looking at their watches," says Zaentz. "He was telling us how he saw the picture with such passion...and as we left, Michael and I were walking on air." Only later, when Michael told his father about the director he'd chosen, did they see what seemed to be the hand of fate. In the mid-'60s, while Kirk Douglas was on a State Department-sponsored tour of Eastern Europe, he met Forman and promised to send him the book, but Forman never received it. It had been intercepted by Communist censors. Says Forman, "I thought, well, these Hollywood big shots twist your head around and promises, promises, then they forget about you. And then later, Kirk told me he thought the same thing. 'This a__hole, I sent him the book and he didn't even say thank you.'"

What Forman didn't know what that Zaentz and Douglas had already met with virtually every other director in Hollywood. The producers set up a meeting with the Czech director at Yamato's -- a Japanese restaurant in Los Angeles' Century City. "We came in about 8 p.m. for dinner and we closed up the joint like in old movies where the waiters circle the table emptying the ashtrays

and looking at their watches," says Zaentz. "He was telling us how he saw the picture with such passion...and as we left, Michael and I were walking on air." Only later, when Michael told his father about the director he'd chosen, did they see what seemed to be the hand of fate. In the mid-'60s, while Kirk Douglas was on a State Department-sponsored tour of Eastern Europe, he met Forman and promised to send him the book, but Forman never received it. It had been intercepted by Communist censors. Says Forman, "I thought, well, these Hollywood big shots twist your head around and promises, promises, then they forget about you. And then later, Kirk told me he thought the same thing. 'This a__hole, I sent him the book and he didn't even say thank you.'"

While Forman and Goldman were pounding out the screenplay, Douglas and Zaentz were running into the same series of slammed studio doors Kirk Douglas had encountered years earlier. "They kept saying, "Who wants to see another Snake Pit?" remembers Douglas. "It wasn't until a lot later that we found out The Snake Pit had been a commercially successful picture. That would have been a good comeback to have had at the time." Adds Forman: "I believe that they just go to a computer and ask it, 'How many films about mental illness made money?' One studio said it was too depressing and had all these suggestions: Maybe if McMurphy doesn't choke the nurse, and maybe if Billy Bibbitt doesn't commit suicide, and maybe if Chief doesn't perform the mercy killing of McMurphy, maybe they would be interested."

While Forman and Goldman were pounding out the screenplay, Douglas and Zaentz were running into the same series of slammed studio doors Kirk Douglas had encountered years earlier. "They kept saying, "Who wants to see another Snake Pit?" remembers Douglas. "It wasn't until a lot later that we found out The Snake Pit had been a commercially successful picture. That would have been a good comeback to have had at the time." Adds Forman: "I believe that they just go to a computer and ask it, 'How many films about mental illness made money?' One studio said it was too depressing and had all these suggestions: Maybe if McMurphy doesn't choke the nurse, and maybe if Billy Bibbitt doesn't commit suicide, and maybe if Chief doesn't perform the mercy killing of McMurphy, maybe they would be interested."

In addition to the production's bleak subject matter, there was something else casting a dark cloud over Cuckoo's Nest -- its disgruntled creator, Kesey. On the first day of shooting, the filmmakers were quickly slapped back into reality by an interview Kesey gave to the local news. According to Goldman, "The interviewer asked Kesey if he went down to the set and Kesey answered, "Does a mother preside over her own abortion?'" Goldman believes Kesey's beef was mainly author's pride and anger that his own script wasn't used. Kesey filed a lawsuit against the filmmakers (which was later settled). But, jokes Goldman, "he had no problem getting his hand out to endorse the checks for his points."

In addition to the production's bleak subject matter, there was something else casting a dark cloud over Cuckoo's Nest -- its disgruntled creator, Kesey. On the first day of shooting, the filmmakers were quickly slapped back into reality by an interview Kesey gave to the local news. According to Goldman, "The interviewer asked Kesey if he went down to the set and Kesey answered, "Does a mother preside over her own abortion?'" Goldman believes Kesey's beef was mainly author's pride and anger that his own script wasn't used. Kesey filed a lawsuit against the filmmakers (which was later settled). But, jokes Goldman, "he had no problem getting his hand out to endorse the checks for his points."