INSIDE OSCAR: 1975

INSIDE OSCAR: 1975

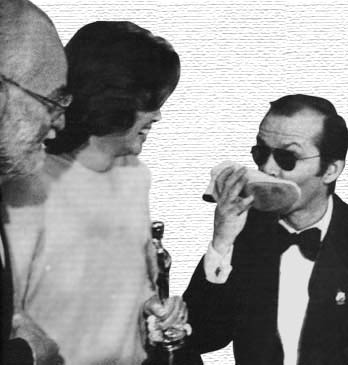

Vengeance was Jack Nicholson's at the 1975 Academy Awards.

Vengeance was Jack Nicholson's at the 1975 Academy Awards.

Before Funny Lady and Tommy could premiere, Pauline Kael was rushing to The New Yorker with an advance review of a musical by Robert Altman. United Artists had financed the director when he said he and Joan Tewkesbury were going to write a movie covering twenty-four characters in a five-day span in country music capital Nashville, Tennessee, but the studio neither understood nor liked the finished script. "Everybody else turned it down, too," Altman said. "I had to get independent financing." Once he got the cash, the director started casting.

Louise Fletcher, who had been in Altman's previous film, Thieves Like Us, was working on a character based on her experience with deaf parents, only to have Altman decide that TV comedienne Lily Tomlin would be perfect for the part. Tomlin admitted that she was skeptical: "When I got the part, I thought, 'I'm not her,' but as I looked at everybody else and saw how perfect they were, I thought Altman couldn't be wrong about me."

Kirk Douglas threw in the towel. After trying for thirteen years to launch a movie version of his 1963 Broadway flop One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, the actor turned over the film rights to his son, Michael, best known for his role as a cop in TV's The Streets of San Francisco. Michael wasn't any more successful than Dad at hustling the property about a nonconformist in a mental hospital, until he took a cue from Michelangelo Antonioni and persuaded Jack Nicholson to star. Douglas was able to raise his $3 million budget independently -- approximately a third of it went to Nicholson -- and hired director Milos Forman, who had left his native Czechoslovakia during the 1968 Soviet invasion and been looking for a Hollywood hit ever since.

Finding an actress willing to play the villainous Nurse Ratched was more difficult -- Anne Bancroft, Ellen Burstyn, Colleen Dewhurst, Angela Lansbury and Geraldine Page all said no. Then Forman looked at Altman's Thieves Like Us to see if Shelley Duvall would be right for the role of a prostitute in Cuckoo's Nest and found himself growing fascinated with the supporting performance of Louise Fletcher, whose husband produced the movie. A week before Cuckoo's Nest started filming, Mrs. Jerry Bick won the role of Nurse Ratched.

The film company retreated to the Oregon State Hospital where "each and every person associated with the production literally lived in the hospital for ten to twelve hours a day during the first three months of 1975," bragged the production notes. Many journalists also happened by the asylum. "Usually I don't have much trouble slipping out of a film role, but here I don't go home from a movie studio, I go home from a mental institution," Nicholson laughed to the New York Daily News, while telling Time, "It's a nice place to visit."

United Artists acquired the film after it was finished, and when Cuckoo's Nest premiered in November, Charles Champlin proclaimed it "the best American film of the year." Rona Barrett predicted "for Louise Fletcher, a sure Best Actress nomination as the bad, life-denying establishment boogiewoman, Big Nurse Ratched." Fletcher, who had only acted on TV before dropping out in 1962 to become a full-time mother, said of her new fame, "Suddenly, I'm having to worry about my hair. I got hot rollers for the first time in my life."

Almost every reviewer brought up the Oscar when evaluating Jack Nicholson's performance, and the New York Times Magazine went out of its way to suggest the actor had all the trappings of a conventional movie star. An article entitled "The Conquering Anti-Hero" stated, "In earning power, he's right up there with Redford and Pacino and probably has surpassed Newman by now. Among producers, he's even more in demand than Gene Hackman for the classic anti-hero roles that went to Bogart and Tracy in the 1940s. He has the standard superstar's house in the chic mountains overlooking Beverly Hills -- with Brando and Charlton Heston as neighbors."

With open season in the Oscar game, film companies campaigned for almost every film released that year. Cuckoo's Nest had the biggest ad push -- seventeen in Daily Variety -- followed by Barry Lyndon with fifteen.

Just who would be nominated caused such concern that the New York Times ran an article in January entitled, "Do Any Of These Actresses Rate An Academy Award?" "There are so few surefire candidates this year that the list may be downright embarrassing," feared Judy Klemesrud, who began the article by suggesting that the relatively unknown Marilyn Hassett might win for the inspirational drama The Other Side of the Mountain. A picture of Louise Fletcher was captioned, "In this weak year, a supporting role may win the Best Actress Oscar for Louise Fletcher." Klemesrud said of Mahogany's Diana Ross, "Some observers say she has a good chance because of sentiment that it is time for a black woman to win."

"In the Best Actress competition, which had attracted special attention this year for what many saw as a dearth of Hollywood candidates," observed Daily Variety, "not one nominee appeared in a Hollywood studio production made in the U.S." The nominees were Louise Fletcher in the independently financed Cuckoo's Nest; Isabelle Adjani in the French The Story of Adele H.; Ann-Margret in the British Tommy; Glenda Jackson in Hedda, a film adaptation of the Royal Shakespeare Company's production of Hedda Gabler; and twenty-two-year-old Carol Kane in Hester Street, an independently made film completed in thirty-four days on a $400,000 budget.

When last year's Best Actress winner, Ellen Burstyn, went on TV and asked Academy members not to vote for Best Actress this year to protest the lack of good roles for women, Louise Fletcher called her up and asked what she meant by it. "She hadn't meant anything personal, but it was personal and my feelings were hurt," Fletcher told the New York Times. "She hadn't even seen Cuckoo's Nest because she felt it would be too painful an experience. I told her that I thought it would have been nicer if she had said what she said in a year when she had been nominated."

Fletcher was also still sore at Robert Altman about being bumped from Nashville. "I must say that he took a part which I inspired and helped to write, and when he got angry with my husband over something else, he gave that part to someone else."

People predicted, "Cuckoo's Nest, the trade figures, should bring Nicholson his long-overdue Oscar and public acceptance as the first American actor since Marlon Brando and James Dean with the elemental energy to wildcat new wells of awareness in the national unconscious." And the five-time nominee assured Rona Barrett he was coming to the show: "I get a kick out of movie stars," he said.

A few stars managed to uphold Hollywood tradition, and at least some of them were sincere about it. Jack Nicholson sported dark glasses with his traditional tuxedo, and brought Anjelica Huston and his thirteen-year-old daughter with him. Michael Douglas explained that his father was in Palm Springs because he didn't want to detract from his son's evening. Cuckoo's Nest director Milos Forman, the winner of the Director's Guild Award, arrived with his twelve-year-old identical twin sons, whom he had not seen since leaving Czechoslovakia in 1968. "The international publicity of the Academy Awards is important to the Communist leaders," Forman said, explaining how his kids were able to visit him. The boys didn't speak English, but they knew the name of their father's film -- "Cuksunext!"

A few stars managed to uphold Hollywood tradition, and at least some of them were sincere about it. Jack Nicholson sported dark glasses with his traditional tuxedo, and brought Anjelica Huston and his thirteen-year-old daughter with him. Michael Douglas explained that his father was in Palm Springs because he didn't want to detract from his son's evening. Cuckoo's Nest director Milos Forman, the winner of the Director's Guild Award, arrived with his twelve-year-old identical twin sons, whom he had not seen since leaving Czechoslovakia in 1968. "The international publicity of the Academy Awards is important to the Communist leaders," Forman said, explaining how his kids were able to visit him. The boys didn't speak English, but they knew the name of their father's film -- "Cuksunext!"

Linda Blair and Ben Johnson stepped out to announce the Best Supporting Actor winner. Milos Forman's sons perked up when they heard the presenters mention "Brad Dourif for One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest." When the winner turned out to be George Burns for The Sunshine Boys, the loud approval of the audience inspired the Forman fils to stand up and applaud their father. "Cut it out," Dad told them. "You are making fools of yourselves. We lost." The boys sat down, confused, while George Burns made his way to the podium.

William Friedkin gave the Thalberg Award to Mervyn LeRoy, who did not dwell on his famous credits, including The Wizard of Oz and The Bad Seed, but thanked the Academy. By now, the Forman boys had lost interest in the show; one was playing with his bubble gum, the other was fast asleep. William Wyler and Diane Keaton, in a suit and tie, stepped out to present the Best Director Oscar, pushing ahead with the nominations. The young Formans snapped to attention when they heard their father's name listed. Wyler announced, "And the winner is Milos Forman for One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest." The boys jumped up and applauded, and Forman raced to the stage, where he explained the secret of his success: "I spent more time in mental institutions than the others." Both of the authors of Cuckoo's Nest were there to claim their Adapted Screenplay Oscars, and Laurence Hauben thanked "some of the finest people I've ever known."

Charles Bronson and his wife, Jill Ireland, announced the Best Actress award. Glenda Jackson was the only missing nominee. The winner was Louise Fletcher, who said of her villainous role in Cuckoo's Nest, "It looks like you all hated me." Then she spoke to her deaf parents in Birmingham, Alabama, via sign language. "I want to thank you for teaching me to have a dream," she said, beginning to cry. "You are seeing my dream come true." For a moment there was total silence, and then thunderous applause.

Art Carney, in a blue tuxedo shirt, followed with the Best Actor envelope. Jack Nicholson still had on his dark glasses. The winner was Nicholson, and the camera saw nominee Walter Matthau mutter to his wife, "It's about time." The audience yelled and whistled as Nicholson hopped to the stage, removing his glasses en route. Art Carney embraced him and Nicholson said, "I guess this proves there are as many nuts in the Academy as anywhere else." He went on to thank honoree Mary Pickford for being "the first actor to get a percentage of her pictures" -- applause -- "and speaking of percentages, last but not least, my agent, who, about ten years ago, advised me that I had no business being an actor."

There was no suspense over the Best Picture outcome. Audrey Hepburn had the responsibility of proclaiming the winner -- One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. Michael Douglas was so excited about his film's sweep of the top five awards, he got his history wrong: "This is the first film to do so since It Happened One Night in 1937." When Douglas and coproducer Saul Zaentz walked off triumphantly, the camera saw a beaming Brenda Vaccaro applauding away.

One who was not so excited about Cuckoo's Nest's sweep was the author of the original novel, Ken Kesey, who said, "I'd like to have subpoenas in some of those Award envelopes." Kesey was suing Michael Douglas for a bigger slice of the profits than he was receiving and was also hurt that no one mentioned him on the Awards show. "Oscar night should have been one of the great days of my life, like my wedding. I really love movies. When they can be turned around to break your heart like this, well, it's something that you never thought would happen."

"God, isn't it fantastic?" was Jack Nicholson's first utterance when he stepped into the pressroom. A reporter asked Louise Fletcher what she thought about the complaints that hers was really a supporting role. "That's a terrible question and a terrible way to end the evening," she responded, but she confessed a few minutes later that she had not received any good film offers since Cuckoo's Nest had opened. As for himself, Michael Douglas predicted, "It's all downhill from here."

Copyright 1986 Ballantine Books.