THE FILMS OF JACK NICHOLSON:

ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO'S NEST

THE FILMS OF JACK NICHOLSON:

ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO'S NEST

A FOUR-LETTER WORD STAR: ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO'S NEST

(1975) A United Artists Release

CAST:

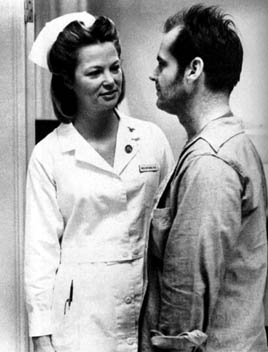

Jack Nicholson (Randall Patrick McMurphy); Louise Fletcher (Nurse Ratched); William Redfield (Dale Harding); Will Sampson (Chief Bromden); Brad Dourif (Billy Bibbit); Marya Small (Candy); Louisa Moritz (Second Hooker); Sydney Lassick (Cheswick); Scatman Crothers (Mr. Turkle); Danny DeVito (Inmate); Dr. Dean Brooks (Dr. Spivey).

CREDITS:

Director, Milos Forman; producers, Saul Zaentz and Michael Douglas; screenplay, Lawrence Hauben and Bo Goldman from the novel by Ken Kesey; cinematography, Bill Butler and William Fraker; editors, Lynzee Klingman and Sheldon Kahn; music, Jack Nitzsche; running time, 129 mins; rating R.

Few films have had as long or troubled a journey from conception to release as this, which ranks along with Gone With the Wind, Jaws, and The Godfather as a classic case of a popular novel being turned into a film no one believed could possibly succeed. Yet somehow, some way, everything turned out right in the end. Cuckoo's Nest swept the Oscars the spring following its release, becoming the first film to take all the major awards since It Happened One Night some forty years earlier.

Few films have had as long or troubled a journey from conception to release as this, which ranks along with Gone With the Wind, Jaws, and The Godfather as a classic case of a popular novel being turned into a film no one believed could possibly succeed. Yet somehow, some way, everything turned out right in the end. Cuckoo's Nest swept the Oscars the spring following its release, becoming the first film to take all the major awards since It Happened One Night some forty years earlier.

That, of course, had been during the studio days, whereas this independently produced feature from Fantasy Films was the brainchild of Saul Zaentz (who would later turn out the equally admirable Amadeus, also directed by Czech Milos Forman) and Michael Douglas, son of Kirk Douglas and soon to emerge as a major producer/star on his own, one of the rare examples of second-generation Hollywood equalling his impressive parent in prestige, power, and performance. Michael had inherited the Cuckoo's Nest property from his father when, after leaving the popular TV police series Streets of San Francisco, the younger Douglas expressed interest in moving into the development and production aspects of motion pictures. Kirk had tried, unsuccessfully, to get a film production of Cuckoo's Nest off the ground since 1962, when he'd first optioned the Ken Kesey novel and appeared in a Broadway version.

But certain elements in society had changed drastically during the preceding decade, making an exact filming of the book a questionable undertaking. Kesey's novel concerned a rebellious man named McMurphy who wreaks havoc in the asylum for the mentally ill in which he's interred, specifically focusing on his conflict with The Big Nurse who has assumed control of the place from the higher-ranking doctors. The McMurphy of the book is very much a Kirk Douglas character: a broad-shouldered, brawling redheaded cowboy/lumberjack/biker, clearly a mythic incarnation of all the American legendary larger-than-life symbols of personal freedom; The Big Nurse is a grotesque caricature, a creature with Jayne Mansfield's bustline and Joan Crawford's cold killer smile. She represents the misogynist's nightmare vision of the female as castrator.

That theme may have gone unchallenged in 1962, but by 1975, the Women's Movement had replaced civil rights and Vietnam as the key social issue of the time. Being good liberals, Douglas and Zaentz didn't want to make a film that would offend a cause they in fact admired; at the same time, they wanted to bring this powerful story to the screen. How to resolve the situation? They realized there would be big problems when such stars as Anne Bancroft, Faye Dunaway, Jane Fonda, and Ellen Burstyn all passed on the role of the nurse, recalling that the celebrated book had recently acquired a reputation for being "sexist." At the same time, Douglas and Zaentz realized that their hero, McMurphy, was as written no longer relevant. Cowboys had all but disappeared from our popular art, TV and the movies; people had, in the cynical seventies, turned their backs on the western loner as our national hero.

And there was a third major problem: Kesey had written Cuckoo's Nest based on his actual experiences as an asylum guard in the early sixties, but while under the influence of certain mind-expanding drugs he'd taken while a creative writing student. The book, told from the point of view of an Indian inmate, perceived the events in surrealistic terms: characters changed shape and form, time stood still, the walls sprouted monstrous arms which tried to grab inmates walking by. There had been an attempt, in the Broadway play by Dale Wasserman, to hint at this by featuring an expressionistic set design and having Chief Bromden (believed deaf and dumb by the hospital staff, though in fact faking both of those handicaps) continually slip upstage, confiding to the audience in asides. But anyone who knows anything about films understands how difficult it is to make such efforts work in a commercial Hollywood picture.

For less ambitious people, these seemingly insurmountable problems may have been incentives to scrap the project. Instead, Douglas and Zaentz (along with screenwriters Lawrence Hauben and Bo Goldman) re-thought the piece, reconsidered its elements, and came up with a script that restructured Cuckoo's Nest for a contemporary audience. They eliminated the battle-of-the-sexes theme by altering the controversial characterization of Big Nurse so completely that her nickname never once appears. Their Nurse Ratched is a softened (rather than overtly menacing) person, who could have been played as either a male or female nurse since there is no mention of gender here. (In fact, a number of the name actresses who turned thumbs down later commented that there was nothing offensive about the portrayal of the nurse in the film version, and felt they'd missed out on an Oscar-winning role.) The book is about the conflict between a man and a woman, and their conflict comes to symbolize the greater battle of the sexes; the movie is about the conflict between two strong-willed people who just happen to be a man and a woman, and their conflict has nothing to do with men and women at all.

What the filmmakers instead concentrated on was the other thread running through the novel: the vision of McMurphy as a symbol of freedom and the nurse as a representation of institutional attitudes. They likewise eliminated the narrator's voice and the surrealist style it necessitated, reducing The Chief to one more character in the drama, thereby freeing themselves to do the film in a near-documentary fashion. The movie was shot not on a Hollywood set's reconstruction of a mental hospital but at Oregon state's hospital at Salem; except for the central characters played by the top-billed stars, the inmates, guards, and physicians seen in the background are real, including hospital superintendent Dr. Dean Brooks as Kesey's muddled if well-intentioned Dr. Spivey.

The ultimate choice, though, had to do with picking the actor who would play McMurphy. The image of him strolling with heroic nonchalance into confrontations with the authorities like a cowboy heading for a High Noon gun duel would have had audiences on their feet and cheering back in the early sixties, but by the mid-seventies would have seemed silly. So all McMurphy's Western-style brag-talk and was eliminated, along with his cowboy boots and a biker's cap that made him appear a second cousin to Marlon Brando's "Johnny" from The Wild One. Instead, he was transformed into a 1970s street person. "Nicholson is far more appropriate for today [than Kirk Douglas]," co-star William Redfield observed. "He's a four-letter-word star."

And that he was: the film rightly earned him his first Oscar and proved a solid hit at the box office, re-establishing Jack at mid-decade as the reigning representative male star of his time. So it's disorienting to realize that at the time of release, most national reviews were negative.

In Time, Richard Schickel saw the film as "faithful to the external events of the novel -- no complaint there." (In fact it drastically changes and reorders those events.) "The trouble is that it betrays no awareness that the events are subject to multiple interpretations...The fault for this lies in a script that would rather ingratiate than abrade, in direction that is content to realize, in documentary fashion, the ugly surfaces of asylum life." To a degree, the complaint is legitimate; the movie does indeed take a single theme from the far more complex book, concentrating exclusively on it. Whereas the McMurphy in the novel could be interpreted (for starters) as an individual against the Establishment, a Christ figure attempting to create disciples for a radical approach to life, or the American male standing up against dominating women, the McMurphy in the film is only the first of these things. Yet the ambiguity that made the book so rich rarely plays within the context of a movie, oftentimes causing a film that attempts such an approach to appear ambiguous and unfocused. Besides, the approximately two-hour running time for a commercial film allows for considerably less levels of meaning than a book that may require twenty hours to carefully read and completely absorb.

Still, most national critics shared Schickel's approach. In Newsweek, Jack Kroll admitted Forman and company had "simplified" Kesey's book "with clarity and shape," but lamented that, "What's lost is the powerful feeling at the center, the terror and the terrifying laughter...By opting for a style of comic realism, Forman loses much of the nightmare quality that made the book a capsized allegory of an increasingly mad reality." Judith Crist, in Saturday Review, acknowledged the movie's impact while sharing such reservations: [This] "is one of those films that are better in the watching than in the retrospect. It is a finely made film, perhaps the most honest to date to deal with a mental hospital...But its subsurface rewards are minimal, its insights as naive as its thesis is obvious." In The Nation, Robert Hatch commented that "Forman's superb dance of fools...leads to nothing beyond its immediate and entirely justifiable goal of superior crowd pleaser. It's impossible not to whoop it up for Cuckoo's Nest while watching, but afterwards, what is one to think?" In The New Republic, Stanley Kauffmann went even further: "The film as a whole is warped, sentimental, possibly dangerous."

Intriguingly enough, Pauline Kael of The New Yorker -- usually the first to seize upon such simplification as justification for demolishing a film -- rushed to the defense, calling Cuckoo's Nest "a powerful, smashingly effective movie -- one that will probably stir audiences' emotions and join the ranks of such pop-mythology films as The Wild One, Rebel Without a Cause, and Easy Rider." Noting that the film seemed more natural, less carefully schematized than the book, she wrote that "even when there are clashes between Kesey's archetypes and Forman's efforts at realism there's still an emotional charge built into the material. It's not as programmed as a mythic trip, yet...this movie achieves Kesey's mythic goal."

Intriguingly enough, Pauline Kael of The New Yorker -- usually the first to seize upon such simplification as justification for demolishing a film -- rushed to the defense, calling Cuckoo's Nest "a powerful, smashingly effective movie -- one that will probably stir audiences' emotions and join the ranks of such pop-mythology films as The Wild One, Rebel Without a Cause, and Easy Rider." Noting that the film seemed more natural, less carefully schematized than the book, she wrote that "even when there are clashes between Kesey's archetypes and Forman's efforts at realism there's still an emotional charge built into the material. It's not as programmed as a mythic trip, yet...this movie achieves Kesey's mythic goal."

Kael also noted that much of the film's impact derived directly from Jack's remarkable performance: "Nicholson is no flower-child nice guy," she asserted, "he's got that half-smile -- the calculated insult that alerts audiences to how close to the surface his hostility is. He's the people's freak of the new stars. His specialty is divided characters...Nicholson shows the romanticism inside the street shrewdness."

Even those critics who thought less of the film than Kael did were quick to point out the power of Nicholson's work in it. Kroll write that, "McMurphy is the ultimate Nicholson performance -- the last angry crazy profane wise-guy rebel, blowing himself up in the shrapnel of his own liberating laughter." In the middle of her string of criticisms, Crist paused long enough to acknowledge that this "may well be the vehicle to win Jack Nicholson his long-deserved Oscar...Nicholson's persona is irresistible, the machismo tempered by a kindliness, the worldliness by a lower-class simplicity." Even Kauffmann admitted "Nicholson is tremendous...in that blue-wool hat and those lounge-lizard sideburns, his eyes smiling; withdrawing; threatening."

Only Schickel, among the key critics, abstained from praising at least the performance. "Jack Nicholson plays McMurphy," he wrote, "as an unambiguously charming figure, a victim of high spirits, perhaps, but without a dark side or even any gray shadings." In fact, the McMurphy of the film is far darker than the agreeable cowboy we met in the book. Kesey's McMurphy was clearly a wonderful, if rough-hewn, hero; there was no room to doubt he was the good guy, or that the sniveling, castrating, uptight, sexually terrified woman he opposed stood as a figure to be ridiculed and, in the end, raped.

In this sense the movie is, despite the catcalls of many critics, in fact more complex than the novel. Though the producers attempted to eliminate the sexual nature of the McMurphy/Ratched conflict, Jack personally felt that it was still there, only in a manner that was less glorifying to the male, less detrimental to women: "It's not in the book," he reflected for the Times in 1986, "[but] my secret design for it was that this guy's a scamp who knows he's irresistible to women and expects Nurse Ratched to be seduced by him. This is his tragic flaw. This is why he ultimately fails. I discussed this only with Louise, that's what I felt was actually happening -- it was one long, unsuccessful seduction which the guy was so pathologically sure of."

In other respects, the movie offers the darker vision: We're never quite sure if this soiled, often unsympathetic McMurphy is as fundamentally decent as he likes to tell the other men on the ward he is, or if the nurse -- sweet, quiet, seemingly sympathetic -- may emerge, at the end, as a decent and misunderstood person. She is not anything of the sort, we finally realize, when she shows her true colors by making Billy (Brad Dourif), the virginal and impressionable self-committed inmate, so guilty about having experienced and enjoyed sex with a prostitute that he takes his own life. Even the ending is darker: The book concluded with McMurphy's lobotomy (at the hands of the nurse, who manipulates the operation to destroy his vitality) and death (at the hands of his friend Bromden, who engages in an act of mercy killing), which sparks the remaining self-committed inmates to go out into the world, where they will try to make it on their own. In the film, Harding and the others are still incarcerated in the hospital after all this has transpired, suggesting McMurphy's sacrifice may have achieved little.

Jack's personal attraction to the vision of Zaentz and Douglas can be seen in this comment: "It's traditional that an American literary personage be in conflict with the authority of some kind or another, and that that conflict is noble. This is what's indigenously interesting about American work. This is traditional literature for America." Perhaps surprisingly, Jack was not specifically referring to Cuckoo's Nest when he offered that remark, but it clearly reveals his affinity for the material. Also relating McMurphy to the canon of Nicholson's films is Kael's comment about the two distinct sides of McMurphy's personality: he is, in that respect, yet another of Jack's varied characters tied by the common thread of establishing double identities. Intriguingly, then, Jack revealed to Helen Dudar that he almost passed on the project: "The starting problem with Cuckoo was that everybody thought I was born to play the part, and in my mind it was going to be very difficult for me. I felt, 'They already think I'm supposed to be great in this, and I'm not sure.' Really, that was almost the main motivation for doing the part...I wanted to allay it, to put it aside."

While shooting the film, he described his view of the character to interviewer Bob Lardine, making clear he saw McMurphy less as a rebel-hero than as a fascinating case study of a death-wish psychotic: "The character I play feigns insanity, and he must be seen through by the audience. Yet this character has a definite mental disorder himself. He behaves in such an anti-social manner that he eventually forces them to kill him."

Jack researched the role by showing up at Oregon State Mental Hospital in Salem two weeks before he was required, where he persuaded hospital authorities to let him mingle with the most disturbed patients, eating in their mess halls and closely observing their speech patterns and body movements. He even watched patients undergoing the same shock treatments McMurphy would be subjected to in the film, in order to make his depiction more authentic. "Usually, I don't have much trouble slipping out of a film role," he admitted, "but here, I don't go home from a movie studio. I go home from a mental institution. And it becomes harder to create a separation between reality and make-believe." That intense association with the character is evident in the remarkable work onscreen. "He is absolutely McMurphy," Milos Forman commented. "Based on this picture, Nicholson is unique among actors in the world today. Nicholson does not exist when he steps before the camera." But Jack modestly credited this actor-oriented director with much of the character's convincing quality: "Milos's angle, which I agreed with, is that the film had to be more real, the behavior less theatrical," than his previous performances.

He understood, though, the controversy their interpretation would provoke among fans of the novel. While making the movie, Nicholson tersely admitted: "Kesey probably won't like the film."

Copyright 1987 Citadel Books.