THE NURSE WHO RULES THE 'CUCKOO'S NEST'

A NEW YORK TIMES ARTICLE

THE NURSE WHO RULES THE 'CUCKOO'S NEST'

A NEW YORK TIMES ARTICLE

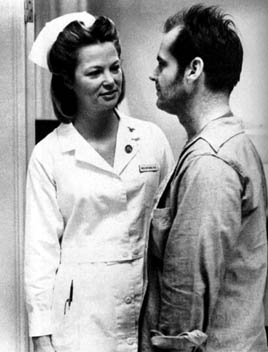

LOS ANGELES -- Smiling a tight little smile, in a toneless voice, Louise Fletcher forces Jack Nicholson to take his tranquilizing medication. With the same smooth, bland expression, she will later order his lobotomy.

LOS ANGELES -- Smiling a tight little smile, in a toneless voice, Louise Fletcher forces Jack Nicholson to take his tranquilizing medication. With the same smooth, bland expression, she will later order his lobotomy.

Louise Fletcher's Nurse Ratched in the movie version of Ken Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest is always calm, always vaguely patronizing, her hair turned under in a perfect Page Boy, a style long out of date. The hair was "a symbol," says Louise Fletcher, "that life had stopped for her a long time ago. She was so out of touch with her feelings that she had no joy in her life and no concept of the fact that she could be wrong. She delivered her care of her insane patients in a killing manner, but she was convinced she was right."

Anne Bancroft, Angela Lansbury, Geraldine Page, Colleen Dewhurst, and Ellen Burstyn turned down the role of Nurse Ratched, most of them because they thought the character was too grotesque a monster. It is Louise Fletcher's achievement that her Nurse Ratched is so close to being a human being that she is totally oblivious of the fact that she is a monster. She is not the physically overpowering Big Nurse of the Kesey novel; she does not wrestle with the mental patients on her ward or shout them into submission. And her approach to the role has been praised by major critics. Pauline Kael, for example, writing in The New Yorker, said, "Louise Fletcher gives a masterly performance... We can see the virginal expectancy -- the purity -- that has turned into puffy-eyed self-righteousness. She thinks she's doing good for people, and she's hurt -- she feels abused -- if her authority is questioned; her mouth gives way and the lower part of her face sags..."

Off screen, Louise Fletcher's hair is windblown. She is 41 years old and has acted only once in the last 13 years. In the late 1950s, she had a brief television career which consisted primarily of Wagon Train, Lawman, and The Untouchables. "I was 5 feet 10 inches tall, and no television producer thought a tall woman could be sexually attractive to anybody. I was able to get jobs on westerns because the actors were even taller than I was." She married producer Jerry Bick and retired in 1962 when she was pregnant with her second child.

She is still more a mother than an actress. It is 4:10 P.M. on a Friday afternoon, and she has just finished driving her fourth carpool of the day. The telephone in her rented Bel Air house rings. The call is from Milos Forman, the director of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. "I never thought they'd get it," he tells her. The "it" to which Forman is referring is the subtlety of her characterization. "Louise had the strength to do it subtle," Forman says in an interview a few days later. "She didn't go for cheap exaggeration. It was the most difficult part in the picture. I was afraid that, surrounded by all those spectacular performances, she would get lost."

It was not easy to resist exaggeration. "Everybody else had so much to do," she says. "When you're being crazy, the sky is the limit. I envied the other actors tremendously. They were so free, and I had to be so controlled. I was so totally frustrated that I had the only tantrum I've ever had in my whole life outside the confines of my own home. The still photographer kept taking pictures of all the crazies and putting them up in the hospital dining room. I asked why he didn't take pictures of me and he said, 'You're so boring, always in that white uniform.' With 6-year-old bitchiness, I went into the dining room and tore down the few pictures he had taken of me."

Milos Forman seems especially pleased with Louise Fletcher's performance, perhaps because he stumbled across her by accident and then fought to get her the part. He was looking at Robert Altman's Thieves Like Us, in which she played the small part of a decent woman who betrays her brother to the police in order to protect her children. A friend had suggested Shelley Duvall, the star of the Altman film, for one of the whores in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. "I was caught by surprise when Louise came on the screen," says Forman. "I couldn't take my eyes off her. She had a certain mystery which I thought was very, very important for Nurse Ratched."

The producers, understandably enough, preferred an actress with a name that might bring a few dollars into the box office. The only role Louise Fletcher had done since 1962 was itself a kind of accident. Her husband was the producer of Thieves Like Us, and she had refused the part because her husband was the producer. She finally accepted when Altman demanded she play the part. "Louise has a very strong Christian southern ethic," says Altman. "She was ideal for the role."

It was after Thieves Like Us that she began to ache to act again. She couldn't even get an agent. She was blonde and beautiful, but she was also 41 years old. Fifteen agents had turned her down by the time Milos Forman sat in a projection room and watched Thieves Like Us.

To prepare for her role of Nurse Ratched, she observed group therapy sessions at Oregon State Hospital, where Cuckoo's Nest was shot. But she herself was part of no group. "I was totally isolated from everybody else in every way. Milos Forman is not one to discuss your role with you. He doesn't want to intrude on you, to invade your space. And I was isolated from the other actors because of the character I was playing. A lot of the time I used to tell the other actors what to order for dinner. That isn't like me to be so controlling. The boy who played Billy couldn't eat. He would leave most of the food on his plate. And I would say, 'Come now. Eat up. You have to eat that, Brad.'"

The other actors began to relate to her as the sweetly bullying Miss Ratched. And there was one appalling moment when the actor playing the hysterical Cheswick refused to do the deep breathing exercises Milos Forman made the actors do before the film's group therapy sessions. "Chessers doesn't feel well today, Miss Ratched,'" he told her, speaking of himself as the character. Instantly, the other actors joined the rebellion against her -- just as the characters in the movie had done -- and Forman had to order them to do the exercises.

Louise Fletcher is no stranger to isolation. As the daughter of totally deaf parents, her whole childhood was marked by a sense of loneliness and separation. "If I fell down and hurt myself, I never cried. There was no one to hear me." Her first day at school, she was sent home with a note to her father saying that since Louise was deaf, he had better send her to a school for the deaf. Her father was angry that her shyness had created the impression she was deaf; he wanted his four children to thrive in a hearing world. To insure that they would learn to speak properly, he sent them -- one at a time -- to Texas to live with his wife's sister. Louise was three years old when she left home for the first time. She stayed in Texas for a year. After that, it was three months a year with the rich aunt in Texas and nine months of poverty at home in Alabama. Her father was an Episcopalian missionary to the deaf. The work was hard and unremitting and he was away from home for weeks at a time. When he was home, he took her with him to visit nearby asylums where the deaf were kept. Her childhood has left its mark in that "mystery" which intrigued Milos Forman. Candid, excruciatingly direct, she has a paradoxical air of reserve, a hidden center.

The sense of emotional isolation she experienced as a child has influenced the choices she has made as an adult. "That's the main reason I gave up my career after John was born and I was pregnant with Andrew. I could not handle going away day after day. The thought of going away before they got up and coming back after they were in bed was intolerable."

Aljean Harmetz specializes in reporting on the film scene.

Copyright November 1975 The New York Times.